Trust me, she asked them. And they did.

It’s the end of 17 grueling weeks, and Associate Professor Crystal Garcia is leading opening ceremonies that mark the final class. But this is no ordinary class. More than half of the students have stored their personal belongings in a locker. They’ve taken off their shoes and belts and have passed security’s scrutiny just to be here.

The other students in attendance just call this home.

Garcia’s J470 seminar in criminal justice is not taking place this May evening on the IUPUI campus. Like the previous 16 classes, this one takes place inside a minimum security prison on Indianapolis’ Near Eastside.

The Indianapolis Re-Entry Educational Facility (IREF) along East New York Street is home to just under 200 Indiana Department of Correction offenders. It’s the last stop before freedom. And it’s a place where they’re given opportunities that will help them make that transition. J470 — a SPEA class that is part of the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program — is one of those opportunities.

For the past five months, Garcia has led 15 Outside students and 11 Inside students on a journey of self-discovery. Tonight is the culmination of that journey.

Other than the drab cinder-block walls and giant Indiana Department of Correction logo painted on the wall, it’s hard to tell the class is taking place in a prison. IREF residents may wear civilian clothes, and many are sharply dressed this night. During a break, one Inside student discusses how he was recently married in this room.

Garcia, a SPEA professor for more than 20 years, is no stranger to teaching behind prison walls. Each fall she leads 50 freshmen in two Themed Learning Community sections called “Dangerous Minds, Dangerous Policies.” The TLC companion speech class and first-year seminar is part of a Toastmasters offering that takes place at a local correctional facility.

But the Toastmasters class is a different experience. Garcia describes it as formal and business-like. It has an agenda, required speeches, and formal evaluations.

“There’s not a whole lot of time for individual side chat; just enough to begin to break down barriers,” she said of Toastmasters.

“With the Inside-Out class, we’re sharing so much more of our personal experiences,” Garcia continued. “We sit in a circle facing each other for three hours every Thursday night, and we’re covering topics that are emotional and will trigger some pain. I just had no idea how much.”

Those topics include race, racism, sexuality, implicit bias, religion, and politics.

“Things you don’t talk about in prison,” she said.

The theme for this semester’s class is “Putting Justice Back into Criminal Justice.” There were numerous readings and weekly journal reflections, and students worked in teams to produce their vision of what a community justice center would look like.

The slogan of the Inside-Out Program is “Social Change through Transformative Education,” and in addition to the demands of a rigorous college course, the semester would also be about changing hearts and minds. And learning to trust.

For Garcia, the semester’s theme is summarized in five simple words. This night, she repeats the phrase to guests nearly a dozen times: “Trust me, and they did.”

“Trust is very important, both for the Inside students and the Outside students,” Garcia said. “But it’s especially true for the Inside students. They are used to being let down by a lot of people. But as long as you do what you say you’re going to do and treat them with respect you’ll eventually get it.

“The bonding happens very quickly if the facilitation is strong.”

Breaking down barriers

As Blaire Viehweg (pronounced vee-wig) rode with friends to the final class of the semester, she “dreaded it.”

This would be the last time she’d see many of these classmates, and she was anxious about getting up in front of the room to give her reflections on the semester. She was one of two Outside students picked to speak at the closing ceremony.

“I had so much in my mind,” the freshman from Greenfield would recount later. “I thought, ‘How can I possibly put this into words?’”

Viehweg spoke openly that night about how the class had intrigued her, engaged her, and ultimately prompted her commitment to being a positive force in the criminal justice system. It marked the end of a transformative year for the freshman who is majoring in criminal justice.

Though she has dreams of working for the FBI, Viehweg admits having previously viewed those behind bars as something out of a Mary Shelley novel.

That view started to change during her first semester at IUPUI when she was enrolled in Garcia’s Toastmasters class. A story related by an IREF participant in the Inside Out Program also struck a chord. Viehweg had never lived on the streets or worried about a meal, but the deeply personal story made her realize that in a split second everything could change.

“It was such an amazing experience the first semester that I didn’t want to stop being the ripple,” Viehweg said. “I wanted to continue planting the seed and rippling out to other people.”

Several months later, as the students were saying their final goodbyes at the Inside-Out class, an Inside student patted Viehweg on the shoulder.

“I’m so proud of you,” he said to her. “I just want to thank you for seeing me as a human.”

The emotions of the night finally hit her.

“That’s what broke me,” Viehweg said. “I was so sad. I told my mom when I was on the way home that I felt like I had lost a family member. That’s the impact they left.

“He’s one of the nicest people I’ve ever met,” Viehweg said of the Inside student. “He changed my point of view, and it made me want to change other people’s view.”

Not just a number

940935.

That Department of Correction number has followed Greg Ousley for most of his life, and to some people that’s all he is – a number. After killing his parents at the age of 14, Ousley has spent the past 24 years behind bars at numerous Indiana prisons. His latest stop is IREF, where he, too, is now before the classroom talking about his Inside Out experience.

He speaks of enlightenment, validation, inspiration, and intervention. The road to this moment hasn’t been an easy one.

“The people in this class showed me they care,” Ousley says. “You guys are the next generation, and that makes me feel good.”

Ousley is no stranger to the classroom. In 2004, he completed a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts through satellite courses at Indiana State University. But those correspondence classes didn’t come with the bonds he made during the past semester.

Early during the semester, while reading about Paula Cooper, Ousley was overwhelmed with emotion. Cooper spent 27 years in prison for a murder she committed when she was just 15 years old. She became the youngest person on Indiana’s Death Row. Her case drew international attention. Her death sentence was ultimately overturned by the Indiana Supreme Court, and Ousley credits Cooper’s case with dissuading authorities from seeking the death penalty in his own case.

In 2015, just days shy of two years since her release from prison, Cooper committed suicide in Indianapolis, taking her life with a single gunshot to the head. Though he knew Cooper’s story, discussing it in such depth drove Ousley from the classroom.

“I knew it was going to be really emotional with Greg,” Garcia said. “I had warned him before the semester started because I was going to use the Paula Cooper book. I didn’t know he had such an affinity for Paula’s situation, but I knew it was similar enough in a lot of ways that it could cause him a lot of angst. It really sent him for a loop.”

Two weeks later, Ousley returned to class. That’s when Bethany Palmer changed his experience for the rest of the semester.

Ousley was the first person Palmer sat next to when class began in January. He exuded a kindness that still makes her smile. The two talked a lot during class and formed a connection that neither expected.

“One day he was talking about all the things he wanted to do when he gets released,” said Palmer. She extended her pinkie to Ousley that day. “I said to him, ‘I want you to promise that you’re never going to hurt yourself.’”

Though Palmer didn’t give the gesture a second thought, it resonated deeply with Ousley.

“It was definitely an intervention for me,” Ousley said. “It was at that moment that I knew the bonds I was making were real.”

Learning not to judge

Before the first Inside-Out class, Jaden Smith already knew that a class behind prison walls would be a transformative experience. Like Viehweg and many of these classmates, both Inside and Outside, Smith had spent a semester with Garcia in Toastmasters.

Within the first couple of Toastmasters classes, he says, his eyes were opened to a new reality. The inmates confined behind chain-link fences and barbed wire were not all monsters. They were men. And eventually they would be our neighbors.

“I changed my views on a lot of things that semester,” said Smith.

Garcia isn’t surprised.

“Everyone goes in with these preconceived notions and biases about what prisoners are, and they learn very quickly that those biases are wrong,” she said. “But it happens on both sides. We start chipping away at these walls that society has put up, and we start to get to know each other as human beings.”

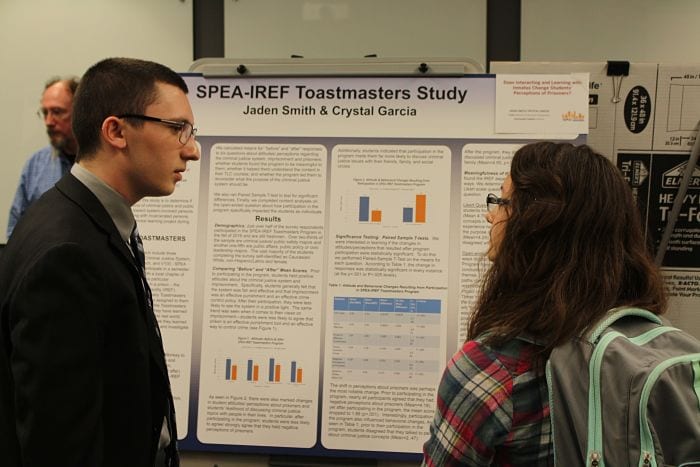

Smith began to wonder whether other students in the Toastmasters program had the same change of heart, so he started working with Garcia to develop a research proposal and questionnaire for current and past students. He surveyed students who had been in the class during the previous two fall semesters and presented his findings at the poster presentations during IUPUI’s annual Robert G. Bringle Civic Engagement Showcase in the spring.

“What we found, to a statistically significant level, is that people were having a shift in their beliefs and their perspectives about inmates,” he said.

While the Toastmasters experience intrigued Smith and pushed him toward the Inside Out class, it didn’t prepare him to deal with such an emotionally charged experience during the spring semester.

“Toastmasters had enough of an effect on me to change my perspective on things, but it didn’t have near the effect that the Inside-Out class had,” Smith said. “It was so much more in-depth, so much more personal. Every class was three straight hours of intense conversation and dialogue.”

Smith said hearing the stories of all the students, especially the Inside students, made him realize you can’t judge people. “You don’t know what they’ve been through.”

“It was very draining,” he said, “but it was also really rewarding.”

Renewed passion

The experience also turned out to be bittersweet. Less than a month after the final class, Indiana officials announced they were closing the IREF facility, a move decried by Garcia and her students.

“IREF really made me want to work in re-entry, and it is discouraging to me how little the criminal justice system focuses on re-entry. There’s not a whole lot of opportunity for it,” said Palmer, who is already working with offenders when she’s not in school. “I’m scared that they’ll ruin the progress they made. I cried when I heard the news. I was hurt they’d close something that’s doing something good.

The class didn’t just have an impact on the students. It also reinvigorated Garcia. At the closing ceremony, she spoke of “falling in love with teaching again.” For anyone who knows her passion for students and the classroom, the comment was surprising.

“The class just got me really excited again,” she explained. “The openness of the students and willingness to take critique and criticism – it was a laboratory that was perfect in terms of a teaching experience.”

In her presentation to the class that spring night, Viehweg said the Inside-Out class had inherently changed the way she views the world. Another student commented that the class wasn’t as much about restorative justice as it was about learning how to be a human being.

“If I weren’t a criminal justice major, I think that class would make me want to be one,” Palmer added. “It was definitely a life-changing experience.”

Being pushed to think critically and the opportunity to interact with people from the outside left an indelible mark on Ousley.

“When you’re on the inside, you’re just doing time. You’re never challenged,” said Ousley, who was transferred to a minimum security prison just beyond the western edge of Marion County. “Being challenged in that way and being accountable is an experience every one of us needs.”

For Garcia, the students’ comments provide affirmation.

“If you really care about what you’re doing in terms of teaching, that’s what you want to see happen,” she said. “It’s not that I want them to change to any particular viewpoint, but I do want to challenge their preconceived ideas in general and to be more open and empathetic to all people. I saw that happen with all of them.”

Trust me, she asked them.

And they did.