To understand SPEA Senior Lecturer Bill Foley’s commitment to combating poverty, look no further than a thick black book that sits in his office. It’s a 600-page dissertation he wrote on urban affairs, including the War on Poverty.

“I didn’t mean to write quite this much,” he laughs. “It made sense at the time.”

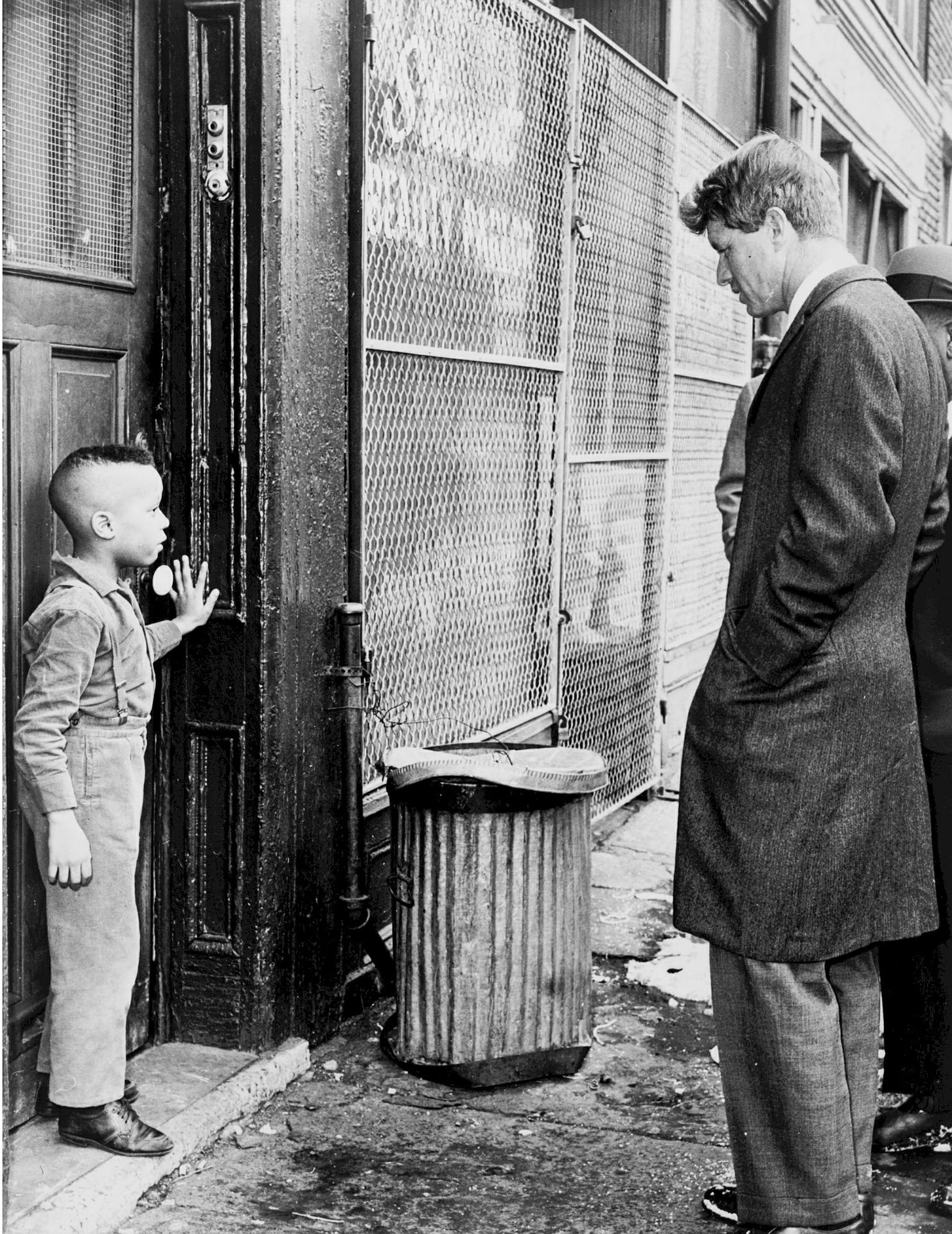

Foley didn’t just write about poverty. He actively worked to support those trying to end it, including volunteering as part of Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1968.

“The Kennedys wanted to do something about poverty,” he says. “They had an idea to bring jobs to those who needed them directly into the inner-city and did so with successful demonstration projects.”

Ideas like those inspired a nation, including Foley and his wife, Mairin. Yet their hope would be dealt an abrupt blow on June 6, 1968.

“We believed, as did Kennedy, that there were solutions that could easily end the disproportionate relationship between urban spending and urban poverty,” Foley says. “Sadly, America never got a chance to find out.”

WHEN MOVEMENTS MERGE

Poverty was not the only issue on the table. Kennedy’s presidential campaign launched during what Foley calls the most divisive time in our nation’s history, post-World War II.

“In the 1960s, there was no compromise between the ballot and the bullet,” he recalls. “Year after year, we saw deadly urban riots and assassinations of political leaders.”

The civil rights movement reached its peak, as the anti-war, women’s rights, and environmental movements all gained momentum.

“It was close to anarchy at times,” Foley says.

But the Foleys, like many others, found hope in Kennedy’s political plans. In addition to taking on poverty, Foley says Bobby carried on JFK’s commitment to making civil rights a moral issue.

“Bobby believed you could not have a government that operated on an irrational premise,” Foley says. “He believed racism was an irrational premise. He also believed a proxy war to save one country by destroying another was irrational.”

As the war in Vietnam raged on, support dissipated, and anger turned into action. Protests erupted around the country. Foley served with the U.S. Army in the central highlands of South Vietnam.

“I buried a lot of friends who served in Vietnam,” he says. “That war needed to end.”

“My generation didn’t take it quietly. We protested and occupied buildings. We were not the silent majority. We got out there and raised hell.”

And they wanted a candidate who would do the same in the political arena.

CAMPAIGNING FOR KENNEDY

The Foleys joined a team of thousands who signed on to work for RFK’s campaign.

“It was all volunteer,” Foley says. “We worked hard and did well.”

They successfully added Kennedy’s name to the Indiana democratic primary ballot, alongside Eugene McCarthy and then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who had Indiana Gov. Roger Brannigan campaign on his behalf.

The move turned the Hoosier state into a battleground state. Indiana played host to numerous campaign stops, including Kennedy’s now famous visit to Indianapolis on May 4, 1968.

That day, Kennedy broke the news of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination to a predominately African American crowd, while calling for calm. As cities across the country faced deadly race riots, Indianapolis did not.

Just two weeks before that day, the Foleys had met Kennedy in person at IU Bloomington.

“It was a pretty radical campus at the time,” he says. “Kennedy won their votes, but it wasn’t a landslide.”

In the end, he also won Indiana. Then Nebraska and then South Dakota. He moved on to win California on June 4, 1968, giving his acceptance speech in Los Angeles in the early morning hours of June 5.

And then, he was killed.

RFK’S ASSASSINATION

The Foleys watched Kennedy’s speech that night from Bloomington. They turned off the TV, only to later hear an abrupt knock on the door.

“It was a neighbor saying Senator Kennedy had been shot,” Foley says. “We turned the TV back on and watched anything we could, until there was nothing more to see.”

Sirhan Sirhan had shot Kennedy as he walked through a hotel kitchen following his acceptance speech. Just two months after MLK was murdered and five years after JFK’s assassination, Bobby Kennedy was gone, too.

Foley says campaign staffers and Kennedy supporters were confused and heartbroken.

“To those who lived in the 1960s, you thought by June 6, 1968, all of the tears had been used up,” Foley sighs. “But that was not the case.”

The emotions many felt went beyond sorrow and anger. It was bigger than that. It was a feeling of profound and far-reaching loss.

“We lost a chance,” Foley says. “A chance for genuine and lasting change to poverty funding. We lost the chance to improve white blue-collar working conditions and wages, and to protect unions. And we lost tens of thousands more lives in Vietnam.”

Foley points to Sen. Edward Kennedy’s eulogy at RFK’s funeral, saying it captured the tremendous sense of loss for what could have been.

“My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life; to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it.

As he said many times, in many parts of this nation, to those he touched and who sought to touch him: Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not.”

THE PAST INFORMS THE FUTURE

After serving in Vietnam then studying poverty, protesting at home, and working in the Kennedy campaign, Foley now educates the next wave of leaders.

In his role as a Senior Lecturer for the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at IUPUI, he teaches about national security, public safety, homeland security, and emergency management. His experiences, the lessons learned, and events witnessed are now part of what he passes on to his students.

Foley says as difficult as it was, it took the 1960s to get us where we are today. And he wants to ensure future generations don’t neglect the lessons learned from the Kennedy campaign and others during that time.

“Understanding our history give students a sense of perspective,” he says. “When people say we haven’t made any progress it simply isn’t true. We’ve made a lot of progress. But we can’t forget the sacrifices made along the way. Today’s progress came with a hefty price tag of many lives, including Martin Luther King’s and Bobby Kennedy’s.”